Standards-based learning is not a program. It is not a system. It is not a new-fangled-next-best-thing kit. It is teaching based on what we know about the brain, about students, and about how to maximize learning. As we become more and more knowledgeable about learning thanks to education research and neuroscience, it becomes our responsibility to use this knowledge to improve what we do. That should not be a choice; when we know better, we need to do better. That means that how we teach should always be changing, just as other professionals change practice based on the newest findings in their fields.

All of the examples on this page were created by your colleagues, who are taking risks and trying to improve how our students learn. Change is not easy, but as the teachers who are making changes will tell you, the results are worth the hard work.

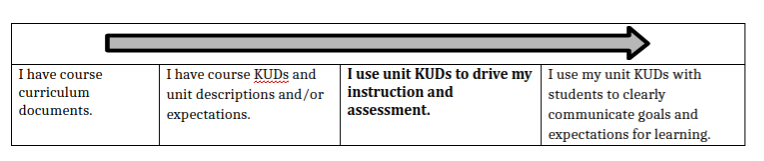

To help with the transition, we have broken SBL into targets with scales. Beneath each we have included an explanation and examples specific to the target. Click on the button here to see the complete targets and scales, or scroll down to look at each individually.

Curriculum: KUDs

The brain wants to know where it's going. In order to learn most effectively, we need clear targets or destinations. Wiggins and McTighe studied the principles of curriculum design years ago, and their findings still remain: students (and adults) need a clear purpose for learning; they need to know where they are going and why they are going there. They developed their findings into one of the most transformational systems in recent education: Understanding by Design, also known as Backward Design. Backward design is the foundation of Carol Tomlinson's work with Differentiated Instruction. The ability to flexibly design and instruct learning opportunities requires a clear destination, or in Tomlinson's language, a KUD. Backwards design is also at the center of standards-based learning. Standards are the destination; they are what we want students to be able to do.

Whether you read Marzano, Wormeli, O'Connor, Wiggins, Fisher, Guskey, the Heath brothers, Jensen or Zull, they all agree on the importance of clarity of purpose.

In other words, this isn't new, and it isn't experimental. Having a clear, articulated goal improves learning.

Whether you read Marzano, Wormeli, O'Connor, Wiggins, Fisher, Guskey, the Heath brothers, Jensen or Zull, they all agree on the importance of clarity of purpose.

In other words, this isn't new, and it isn't experimental. Having a clear, articulated goal improves learning.

Here at CVU, we have already embraced the power and importance of the KUD. All teachers have course KUDs, and most are now using unit KUDs. It's at the unit level that the KUDs can really help drive learning. Here are a few examples from your colleagues:

- 10th grade humanities: unit on rhetoric

- 9th grade science: unit on scientific practices

- British Literature: unit on the Bluest Eye

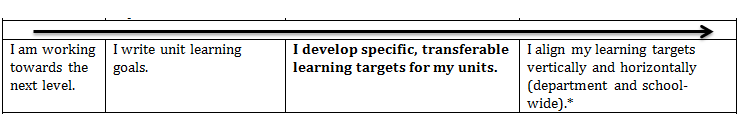

Curriculum: Targets and Scales

Within a unit, students need to have more specific targets for their learning than the course or school or national standards. While the standards (ESLs, CCSS, NGSS, etc.) can provide our ultimate destination looking at a body of work over time, they are usually not very helpful (for us or for students) when it comes to specific instructional design and assessment. Learning targets, in contrast, are precise and specific to our discipline areas and/or grade levels. They are meant to provide a specific destination for learning within our units or classes.

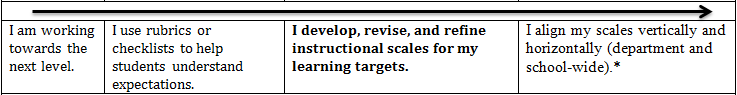

Scales are rubrics of sorts, only they are meant to guide learning as well as assess achievement. A scale shows the continuum of learning. It allows for specific feedback and the development of activities, practice and assessments at a variety of levels. We know that students learn best when working in their ZPDs, and scales help teachers and students plan for the variety of readiness levels in our classes.

It's important to word all levels of the scale in language that shows what the student can do, not what he/she can't do (I can language...). This is not everybody-gets-a-trophy feel-good philosophy. Learning happens on a continuum--skills grow and continue to improve over time and with practice, and when students see that learning is a progression (not a got-it or didn't), they are more likely to stick with it when it gets difficult.

Here are some examples of scales designed by your colleagues. Please note that these are all drafts and are being revised as they are being used in order to make them more accurate and useful.

Scales are rubrics of sorts, only they are meant to guide learning as well as assess achievement. A scale shows the continuum of learning. It allows for specific feedback and the development of activities, practice and assessments at a variety of levels. We know that students learn best when working in their ZPDs, and scales help teachers and students plan for the variety of readiness levels in our classes.

It's important to word all levels of the scale in language that shows what the student can do, not what he/she can't do (I can language...). This is not everybody-gets-a-trophy feel-good philosophy. Learning happens on a continuum--skills grow and continue to improve over time and with practice, and when students see that learning is a progression (not a got-it or didn't), they are more likely to stick with it when it gets difficult.

Here are some examples of scales designed by your colleagues. Please note that these are all drafts and are being revised as they are being used in order to make them more accurate and useful.

- Intro to Art: unit on line drawing

- Geometry: unit on constructions and similarity

- Media Literacy: scales for all units

- Physics: unit on Work and Energy

- Spanish: all units for Spanish 2

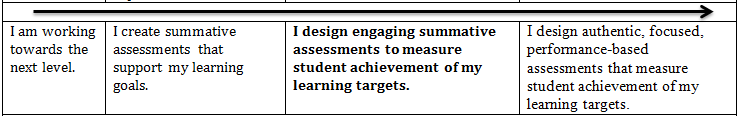

Instruction and Assessment: Summative Assessments

Designing summative assessments before beginning the unit continues to support what we know about backwards design. When we know what the end game will be, we can design our practice opportunities and instruction to prepare kids for success. It's important to remember that we want all students to excel on the summative; we are successful if they are successful. Here are a few important reminders about summative assessments:

Here are some examples of standards-based summative assessments from your colleagues. Notice how the targets are explicitly provided for the students and how the goal is to provide an accurate assessment of achievement, not tally points:

- Summative should be intentionally designed to assess the learning targets: the purpose of a summative is to assess what students know, understand, and are able to do at the end of a unit. This is an opportunity for students to show us what they learned, and an opportunity for us to see how successful we were with the unit. In order to get good information, the summative needs to be aligned to the same targets that have driven our instruction and practice.

- Summatives should match practice: students need opportunities to practice in the way they will be assessed. If you want them to be able to transfer understanding, then make sure they have practiced doing this before the assessment.

- There shouldn't be any surprises: by the time our students take the summative, we should know how they will do. Because we have been monitoring practice and providing feedback along the way, and because the summative matches what we have practiced, we should be able to fairly accurately anticipate which students will struggle and which are ready for success. Knowing this along the way allows us to differentiate instruction and practice leading up to the summative in order to ensure all students are prepared.

- Re-dos and re-takes may be necessary: if a student's achievement on the summative does not match what you have seen during the rest of the unit, then something is wrong. Our job is to be able to accurately communicate what a student knows, understands, and can do within the unit. If the summative scores are not accurate, then it's our responsibility to find out why. This is when a conversation, a retake, or a revision would be mandatory. If, however, the summative matches the practice, a revision or retake would not make sense--we have no reason to believe (based on evidence we have seen and provided feedback on) that the student knows, understands, or can do more than the summative demonstrated, and so we would not allow a revision or re-take.

Here are some examples of standards-based summative assessments from your colleagues. Notice how the targets are explicitly provided for the students and how the goal is to provide an accurate assessment of achievement, not tally points:

Practice, Formative Assessment, and Feedback

The bulk of our time as teachers should be spent designing engaging, targeted practice for students. For most of us, this is the hardest, yet most rewarding part of teaching as well.

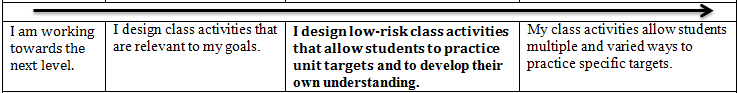

Once we have established our unit specific targets and have determined the content we want to (or have to) use to get to those targets, we need to allow students to practice. Learning takes time, and the best learning will require plenty of opportunities to try, fail, get feedback, and try again. That's why these activities, assignments, and formative assessments need to be low risk. Students very quickly learn that it's not okay to take risks with learning when they are being graded on each attempt. When we grade their early attempts we are showing them that we value "being right," not learning. This leads to stress, low risk taking, and even cheating. Remember what it's like to learn something new--the only way to get better is to try, fail, and try again. None of us would be able to play the guitar, ski, act, dance, read, cook, or teach if we hadn't failed along the way but kept going; it's the same in our classes.

The practice that we design needs to be targeted, and it should look as much like our summative as possible. When preparing for Spamalot, the director doesn't just ask students to stand on stage and sing; she provides them the songs that will be in the final performance. She doesn't have them speak the lyrics during rehearsal; she has them sing, just as they will do for the final performance. And she doesn't ask students to sit in a classroom and read their lines to each other over a desk; she has them get up and move as they will in the final performance. In other words, the instructor should try to mimic the conditions of the summative in order to truly prepare students for what we will be assessing. That said, it's necessary to "shrink the field" during practice (i.e. focus on one part of one scene during rehearsal, not continuously running through the entire play) so that we can really pinpoint a particular part of the learning.

Here are some sample activities from your colleagues. These tasks are all target-based:

Once we have established our unit specific targets and have determined the content we want to (or have to) use to get to those targets, we need to allow students to practice. Learning takes time, and the best learning will require plenty of opportunities to try, fail, get feedback, and try again. That's why these activities, assignments, and formative assessments need to be low risk. Students very quickly learn that it's not okay to take risks with learning when they are being graded on each attempt. When we grade their early attempts we are showing them that we value "being right," not learning. This leads to stress, low risk taking, and even cheating. Remember what it's like to learn something new--the only way to get better is to try, fail, and try again. None of us would be able to play the guitar, ski, act, dance, read, cook, or teach if we hadn't failed along the way but kept going; it's the same in our classes.

The practice that we design needs to be targeted, and it should look as much like our summative as possible. When preparing for Spamalot, the director doesn't just ask students to stand on stage and sing; she provides them the songs that will be in the final performance. She doesn't have them speak the lyrics during rehearsal; she has them sing, just as they will do for the final performance. And she doesn't ask students to sit in a classroom and read their lines to each other over a desk; she has them get up and move as they will in the final performance. In other words, the instructor should try to mimic the conditions of the summative in order to truly prepare students for what we will be assessing. That said, it's necessary to "shrink the field" during practice (i.e. focus on one part of one scene during rehearsal, not continuously running through the entire play) so that we can really pinpoint a particular part of the learning.

Here are some sample activities from your colleagues. These tasks are all target-based:

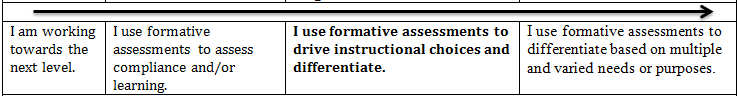

The choices we make when designing our practice activities and instructional choices need to be based on what we know about where students are in relation to the targets. Formative assessments (which can range from quizzes to exit cards to discussions to observations to classwork) give us this information. Let's say I have a class activity that involves students working in groups to gather research based on a provided thesis. The target that they are focusing on is about using the best evidence to support a thesis. Here's how I might formatively assess: 10 minutes before the end of class, I will hand out an index card. I will ask students to write the one piece of evidence that they think is the best on one side, and a piece of evidence they think is not very good on the other; then I will ask them to explain why they chose each based on the thesis. That's it. It's important that this is done individually--it's okay (even beneficial) to have students work in groups often, but our assessment of their knowledge, understanding or skill needs to be individual.

Now that I have the index cards, it will take me 5-10 minutes to go through them and put them in 3 piles: those that nailed it, those that are close, and those that aren't there yet. This is the start of my planning for the next class. In order to ensure that all students are going to meet the target, I am going to need to differentiate my next practice around evidence. I may decide to spend 30 minutes the next class on this target again--and I know I need to design 3 opportunities. The first will most likely be some reteaching or further instruction (and this is the group I may need to spend the bulk of that 30 minutes with); the second will probably be a little more targeted practice--preferably individual as that will be more efficient; and the third will be an opportunity to approach the target with more complexity or nuance--designed to be student driven so that I can focus my attention on the re-teaching.

Not every differentiated lesson should look this way. There are times when I want to spend 30 minutes challenging those that are ready to move on; if that's the case, I design an activity that allows practice or modeling for those that need more work on getting towards the target.

Because you are basing your groupings on specific, targeted data (your formative assessments), this is not "tracking." Teachers new to differentiation often get nervous about readiness grouping, thinking they are tracking students. They worry that kids will feel bad being in the "dummy group." When you are grouping based on specific data and precise targets, this doesn't happen. Students know that you are providing each group what they specifically need to progress in that target. It's vital that you don't just give busy work to the groups you are not directly working with, however; all students deserve to be challenged.

Differentiation is probably the most difficult, but most important part of our job as teachers. We cannot ensure learning if we don't differentiate; and we cannot differentiate if we don't have specific and targeted data to work from. It takes practice to feel comfortable grouping students, managing multiple groups, designing multiple activities, and talking to students about learning. But getting better at this skill is vital to our success--and therefore student success--so must keep trying.

Now that I have the index cards, it will take me 5-10 minutes to go through them and put them in 3 piles: those that nailed it, those that are close, and those that aren't there yet. This is the start of my planning for the next class. In order to ensure that all students are going to meet the target, I am going to need to differentiate my next practice around evidence. I may decide to spend 30 minutes the next class on this target again--and I know I need to design 3 opportunities. The first will most likely be some reteaching or further instruction (and this is the group I may need to spend the bulk of that 30 minutes with); the second will probably be a little more targeted practice--preferably individual as that will be more efficient; and the third will be an opportunity to approach the target with more complexity or nuance--designed to be student driven so that I can focus my attention on the re-teaching.

Not every differentiated lesson should look this way. There are times when I want to spend 30 minutes challenging those that are ready to move on; if that's the case, I design an activity that allows practice or modeling for those that need more work on getting towards the target.

Because you are basing your groupings on specific, targeted data (your formative assessments), this is not "tracking." Teachers new to differentiation often get nervous about readiness grouping, thinking they are tracking students. They worry that kids will feel bad being in the "dummy group." When you are grouping based on specific data and precise targets, this doesn't happen. Students know that you are providing each group what they specifically need to progress in that target. It's vital that you don't just give busy work to the groups you are not directly working with, however; all students deserve to be challenged.

Differentiation is probably the most difficult, but most important part of our job as teachers. We cannot ensure learning if we don't differentiate; and we cannot differentiate if we don't have specific and targeted data to work from. It takes practice to feel comfortable grouping students, managing multiple groups, designing multiple activities, and talking to students about learning. But getting better at this skill is vital to our success--and therefore student success--so must keep trying.

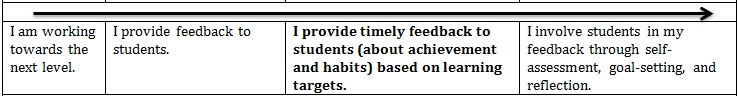

Feedback is vital to learning. We cannot improve without feedback. But feedback does not have to mean hours and hours making comments on work. In fact, research shows that this is almost always an inefficient and ineffective way of providing feedback (Fisher and Frey). Good feedback should be timely, specific, and should involve student action.

Feedback needs to be timely. The best feedback is immediate. Think of learning how to juggle. You take three balls and throw them all into the air. You catch one, but the others fall. Immediate feedback--it didn't work. You try again, this time, holding onto one and throwing the other two in the air. You fail again. Immediate feedback. How did you know you failed? Because you know what it looks like when someone succeeds at juggling. You can see the target and you compare yourself to that target right now. You don't have to wait a week to find out how you did. Video games are success for this very reason--they provide clear, immediate feedback; players know the goal (get to level 2) and watch themselves progress (or lose a life).

How do we bring that immediacy into the classroom? By changing our definition of feedback. We do not need to collect everything and grade everything and comment on everything. Instead, we need to design practice opportunities and a class structure that allow us to see the learning and provide feedback (a quick comment, a redirection, small group instruction, targeted practice) as soon as possible. That means that class should be the time when students are doing and we are watching them do. Does this mean "flipped" classes where we deliver content outside of class? No. It means rethinking how we use our time so that students access our content by doing more than by being receptacles to our delivering. For example, rather than giving a lecture or powerpoint about the Boxer Rebellion or Photosynthesis, provide them a thesis statement and 3 resources and have them find the evidence themselves. They do the learning and you watch, redirect, correct misconceptions, and provide immediate feedback. At the end of this class you can collect their notes, sort them into 3 piles, and really target your instruction the next day based on student need.

Think of all the time you will save grading everything and commenting on everything. And instead, you can spend that time planning meaningful and when necessary, differentiated, practice.

Feedback needs to be timely. The best feedback is immediate. Think of learning how to juggle. You take three balls and throw them all into the air. You catch one, but the others fall. Immediate feedback--it didn't work. You try again, this time, holding onto one and throwing the other two in the air. You fail again. Immediate feedback. How did you know you failed? Because you know what it looks like when someone succeeds at juggling. You can see the target and you compare yourself to that target right now. You don't have to wait a week to find out how you did. Video games are success for this very reason--they provide clear, immediate feedback; players know the goal (get to level 2) and watch themselves progress (or lose a life).

How do we bring that immediacy into the classroom? By changing our definition of feedback. We do not need to collect everything and grade everything and comment on everything. Instead, we need to design practice opportunities and a class structure that allow us to see the learning and provide feedback (a quick comment, a redirection, small group instruction, targeted practice) as soon as possible. That means that class should be the time when students are doing and we are watching them do. Does this mean "flipped" classes where we deliver content outside of class? No. It means rethinking how we use our time so that students access our content by doing more than by being receptacles to our delivering. For example, rather than giving a lecture or powerpoint about the Boxer Rebellion or Photosynthesis, provide them a thesis statement and 3 resources and have them find the evidence themselves. They do the learning and you watch, redirect, correct misconceptions, and provide immediate feedback. At the end of this class you can collect their notes, sort them into 3 piles, and really target your instruction the next day based on student need.

Think of all the time you will save grading everything and commenting on everything. And instead, you can spend that time planning meaningful and when necessary, differentiated, practice.

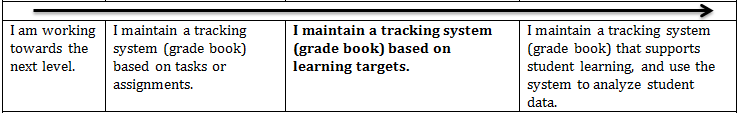

Grade Book

The standards-based grade book tracks learning. Most traditional grade books track assignments and compliance. The biggest visual difference is what is across the top of the grade book. In both, the students' names are down the left hand side of the grade book. In a traditional, the assignments or tasks are across the top with a number of associated points. For example, "Quiz on Revolution (10 points)". The traditional is straight-forward (or seems so...): Carly takes quiz, gets a 7/10, so I put a 7 in the box under Quiz on Revolution. At the end of the quarter, I (or the computer) add up all the points, divide by the total, and spit out a mathematically "accurate" grade. Easy. But what does that tell me about learning? Not much.

In a standards-based grade book, the learning targets are across the top. For example, "Analyze an author's use of rhetoric". And what gets entered? Any evidence of learning for that target. (Note: We are using a 1-4 scale, but some schools use "Meets/Exceeds" language, and others random symbols.) There may be 4 tasks that address this target throughout the unit, and so each of those gets entered under the target. At the end of the unit (not quarter), I (or JumpRope, the computer program we use) determines the most accurate assessment of the student's achievement of that target based on trends and/or most recent evidence of learning. Easy. What does it tell us about learning? A lot.

The standards-based grading program we are using, JumpRope, was design specifically by educators for this work. It allows us to easily track learning by target, but to enter that learning by task. Those of you moving to SBL in your class or classes next year will be trained in JumpRope in August, but we encourage you to go to www.jumpro.pe to explore the site and capabilities.

In a standards-based grade book, the learning targets are across the top. For example, "Analyze an author's use of rhetoric". And what gets entered? Any evidence of learning for that target. (Note: We are using a 1-4 scale, but some schools use "Meets/Exceeds" language, and others random symbols.) There may be 4 tasks that address this target throughout the unit, and so each of those gets entered under the target. At the end of the unit (not quarter), I (or JumpRope, the computer program we use) determines the most accurate assessment of the student's achievement of that target based on trends and/or most recent evidence of learning. Easy. What does it tell us about learning? A lot.

The standards-based grading program we are using, JumpRope, was design specifically by educators for this work. It allows us to easily track learning by target, but to enter that learning by task. Those of you moving to SBL in your class or classes next year will be trained in JumpRope in August, but we encourage you to go to www.jumpro.pe to explore the site and capabilities.

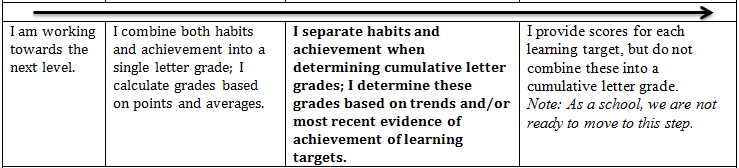

Determining Grades

The idea for SBL is to stop at the previous target. When we try to consolidate evidence of learning into a single indicator of achievement, the less accurate--and therefore the less meaningful--it becomes. Giving a single grade dilutes the clarity of communication.

That said, we are working within a system (local, state-wide and national) that still expects a single grade for each learning experience (i.e. unit, quarter, course). So our responsibility is to make that grade as meaningful and consistent as possible within the parameters.

Grades are communication, not compensation. In a standards-based system, students don't "earn" grades. Teachers do not use grades to reward or punish. Grades are simply the symbols we apply to communicate achievement of a target (or in our case, a set of targets). Yes, this is a significant mindset shift, but it's a vital one as long as we continue to use grades.

For the 2014/2015 school year, we will finally have the ability to report 2 separate grades for each course: an achievement grade (based solely on the academic targets for the course), and a habits of learning grade (based on the habits targets for the course). This is an important step forward for us as a school. In order for this to be meaningful, we need to think of habits as we do skills--we need to instruct them and provide feedback to students--not just use them to punish and reward bad or good behavior or habits as we see them. We currently have a school-wide habits ESL, but this will surely be revised as we all begin instructing and reporting over the next year. In addition to the school-wide habits ESL, many departments or programs have worked hard to define the habits essential for success: the arts department, the core, and the 10th grade teams have all drafted habits targets and/or scales.

That said, we are working within a system (local, state-wide and national) that still expects a single grade for each learning experience (i.e. unit, quarter, course). So our responsibility is to make that grade as meaningful and consistent as possible within the parameters.

Grades are communication, not compensation. In a standards-based system, students don't "earn" grades. Teachers do not use grades to reward or punish. Grades are simply the symbols we apply to communicate achievement of a target (or in our case, a set of targets). Yes, this is a significant mindset shift, but it's a vital one as long as we continue to use grades.

For the 2014/2015 school year, we will finally have the ability to report 2 separate grades for each course: an achievement grade (based solely on the academic targets for the course), and a habits of learning grade (based on the habits targets for the course). This is an important step forward for us as a school. In order for this to be meaningful, we need to think of habits as we do skills--we need to instruct them and provide feedback to students--not just use them to punish and reward bad or good behavior or habits as we see them. We currently have a school-wide habits ESL, but this will surely be revised as we all begin instructing and reporting over the next year. In addition to the school-wide habits ESL, many departments or programs have worked hard to define the habits essential for success: the arts department, the core, and the 10th grade teams have all drafted habits targets and/or scales.

- Core Habits of Learning Scales

- Proposed Revision for Habits from Arts Department

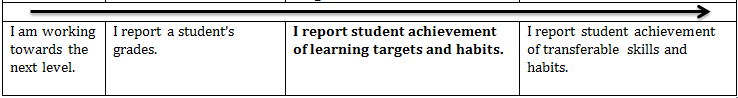

Reporting Learning

Even though we still need to give a single grade for learning (and even more so because we have to), it's vital that we report as accurately as possible where our students are in relation to our targets. There are multiple audiences for this reporting, the student, the teacher, the parents, and maybe eventually, colleges or employers.

First, the student needs to know. Learning occurs when you have a clear target, when you know where you are in relation to that target, and when you know how to close the gap between the two. Clear reporting can provide that clarity (and accountability) for students. The more specific the reporting is for the students, the better.

Second, the teacher needs to know. The more specific the data, the better we will be able to respond to it. By having clear and specific reports, we hold ourselves accountable to the learning. We can't just say, "work harder." We need to act on the specific and precise information we have out learning.

Third, the parent needs to know. There is some debate among experts about the level of detail the parents need on a regular basis. For example, many say that parent reports should be at the standard level (Reading Analysis) and do not need to be at the more specific target level (Analyzing and author's use of rhetoric); others say why not provide the level of detail we have. This is something we will have to determine as we move forward--how much information is too much information?

And finally, eventually, colleges and employers may want to know. If we get to a point where we can accurately assess the standards and report on a limited number of them, we may move towards a true standards-based transcript. Currently, we are reporting standards/targets at the unit and course level only, though our transcript will include two "grades" for each class, and two cumulative GPAs, one for academic achievement, and one for habits of learning.

First, the student needs to know. Learning occurs when you have a clear target, when you know where you are in relation to that target, and when you know how to close the gap between the two. Clear reporting can provide that clarity (and accountability) for students. The more specific the reporting is for the students, the better.

Second, the teacher needs to know. The more specific the data, the better we will be able to respond to it. By having clear and specific reports, we hold ourselves accountable to the learning. We can't just say, "work harder." We need to act on the specific and precise information we have out learning.

Third, the parent needs to know. There is some debate among experts about the level of detail the parents need on a regular basis. For example, many say that parent reports should be at the standard level (Reading Analysis) and do not need to be at the more specific target level (Analyzing and author's use of rhetoric); others say why not provide the level of detail we have. This is something we will have to determine as we move forward--how much information is too much information?

And finally, eventually, colleges and employers may want to know. If we get to a point where we can accurately assess the standards and report on a limited number of them, we may move towards a true standards-based transcript. Currently, we are reporting standards/targets at the unit and course level only, though our transcript will include two "grades" for each class, and two cumulative GPAs, one for academic achievement, and one for habits of learning.